I would be remiss if I didn't include a blog post on one of my weirdest specialties: colorful meditations with dead composers. So I leave you with this final blog post on the motet puppet show, at least for the time being. I sat down to try a meditation conversation with Johann Sebastian Bach and asked what he might have to say on creativity, productivity, and the motets. Here are the results. I see a watering can held by an unseen hand slide through the crown glass window to give the flowers in the window box a drink. To my left is a large wooden door, so I knock. Mr. Bach opens the door and beckons me to come in. Then I see the owner of the watering hand, and it’s Anna Magdalena! She’s smiling and very welcoming. I find myself inside a cozy cottage beside a milk jug full of flowers. I sit on a carved wooden bench facing Anna and Johann who sit in their own chairs beside a crackling fire. Anna picks up her knitting and Johann starts puffing on his pipe. “Thank you so much for inviting me in to speak with you,” I say, “While I called upon Johann, it’s marvelously unexpected to meet you too, Anna!” She giggled, “This American habit of calling people by first name is certainly strange!” I realize it’s strange too to call Bach “Johann" considering all his relatives were named Johann, but that’s what my mother called him, so it stuck. “You wanted to talk to me about something,” Johann says. “What specifically do you have in mind?” “As you know I’m working on a shadow puppet show to go along with your motets, so I wanted to see if you had anything to share with the public about the motets, or creativity, practice, and productivity. I mean, really anything you have to say would be amazing!”  A wine label I designed for a Seattle Bach Choir fundraiser. He wasn't wearing a toga in this meditation, but this is kind of how I see him. A wine label I designed for a Seattle Bach Choir fundraiser. He wasn't wearing a toga in this meditation, but this is kind of how I see him. Anna lit up, “A puppet show! Oh, that sounds very exciting!” Johann puffed on his pipe thoughtfully without saying a word. I kind of wondered where all the children were, but of course they had all grown up a long time ago. I had another curiosity as well. Often when I reach out in meditation to certain personalities they have large castles built upon their desires and concepts of their own self worth. Why was I in a cottage? I asked Johann if he had a castle and why we weren’t there, not that I would rather be in a castle, I was just curious. “We thought this would give you a more welcoming, homey feeling,” he said. True enough. Johann then took a big drag on his pipe and blew out a cloud of smoke which held a picture. Within the cloud was a racing horse, but standing completely still in mid gallop. The edges of the horse were streaking, with gaps between the lines. The horse, paused in motion, appeared to be an incomplete specter. “The funny thing about music is that it is an ungraspable art form,” Johann explained. “It speeds by, but it leaves gaps. It is never complete. Music is only ever completed in the listener’s mind, and we all complete it differently.” He got up and led me to another room, the music room. On my right a viola da gamba lay on its side on the floor. On my left was a harp beside a couple of bookshelves, and before me was a red oriental carpet and a gray harpsichord outlined in gold. Johann sat at the harpsichord and began to play one of his fastest pieces from the Well Tempered Clavier Book 1: the prelude in C minor. It became the horse, running for me in shades of indigo blue, slate gray, and mustard yellow. Johann then got up and went to one of the bookshelves. He handed me a large book bound in mauve silk, but I didn’t open it just yet. "Seems to me that any art form that makes use of time is ungraspable,” I said, “all performance art certainly, but maybe even visual art and written art. We all perceive based upon our own experiences and mindset.” “Yes, art comes to life only within the observer. The best we can hope for as artists is that we can inspire others,” Johann said sounding strangely like John Cage. I opened the book and saw another illustration of a horse in pen and ink. The horse stood within its stable as a farm girl offered it an apron full of hay. Johann explained. "As artists though we must feed our audience good food. Horses have a limited diet. That’s why they don’t compose sinfonias.” I snickered. “Tell me about your motets. I find it interesting that they were the only pieces of yours that were consistently performed after your death.” “That’s because they’re functional. People care much more for function than for art.” He then sat back down at the harpsichord and began playing Komm, Jesu, komm. A slight smile formed upon his face, like he was reliving a beautiful memory. “How did you feel about your motets?” I asked. “Did you like what you created?” “I’ll tell you this. It doesn’t matter what I think of them. Does it matter how the giver feels about the gift he gives another? What matters only is how the receiver feels about it. When we belittle our own art we must be mindful that there is always someone less advanced who may be discouraged by that.” I nodded in agreement. I know it bothers me when one of my artistic heroes hates their own work. If that’s the case then they must surely hate my work too!  A rose puppet from Lobet den Herrn cut from adhesive vinyl and attached to a pink gel. You can even see the pencil lines. A rose puppet from Lobet den Herrn cut from adhesive vinyl and attached to a pink gel. You can even see the pencil lines. “I have another more personal concern,” I said. “Once I perform this show I may not be able to put on another large scale puppet show for a long time. I’ll be losing my rehearsal space, and these productions take so long to create I can never make enough money from them to make it out of poverty. But at the same time I’m going to gain momentum from this show. I don’t want to waste it. What do I do with that momentum?” Johann showed me a sled sitting at the top of a snowy hill, a very steep hill. My heart was in that sled feeling trepidation about going down that hill, but I did. Going down hill allowed me to gather up the speed required to float up the next hill effortlessly. I then sat upon that next hill feeling that same fear about going down the other side. This message was more felt than heard. I can use that momentum in any way that feels right at the time. It doesn’t have to be put into another large scale puppet show, or even a puppet show at all. The hardest part though is pushing yourself down that hill to start gathering the momentum needed to overcome your obstacles, but I’m doing it. It’s all about having the bravery to start something in the first place. I began to open my eyes, but Johann called me back saying he had something else to say. I saw an hourglass, but it was shaped differently, like two pyramids on top of one another point on point. Johann took a bag of sand and started pouring it into the hourglass. “You can always add more sand,” he said. “Come on, you can’t just add time,” I quibbled. “But you can! Time isn’t real, and above all it is what we make of it.” “I don’t know how much of that I can understand, but I do know this...” I said as I reached into the hourglass. I built a little sandcastle, destroyed it, then built another. “This must be what music is: to build sandcastles in the hourglass.”

0 Comments

A paper perch A paper perch Komm, Jesu, komm is possibly Bach’s most tender and passionate motet. It is another funeral motet, but we don’t know for whom, though it may have been written for the funeral of the theologian Johann Schmid who died in 1731. We do know that the motet was written sometime before 1732 in Leipzig. There is no autograph of this motet, and the only reason we have it at all is because Christoph Nichelmann, a student of Bach’s and accomplished composer in his own right, copied it in 1732. The poet of the text, Paul Thymich, a professor at the Thomasschule where Bach was cantor, wrote the poem for another funeral, that of the philosopher Jakob Thomasius in 1684. On that occasion Johann Schelle, Bach’s predecessor as cantor, composed the music to this text. Schelle’s work is fairly simple for one choir in five voices, but uses the whole text. Bach’s version uses only the first and last stanzas and spins those out mainly in double choir format through several sections and variations. The longest section accompanies the words “du bist der rechte Weg, die Wahrheit, und das Leben,” or “you are the way, the truth, and the life,” and is an extended back and forth between choir one and choir two. You can hear Schelle’s version here and follow along with the score.  A diving osprey A diving osprey This is also one of Bach’s more “modern” sounding works. It looks forward to the gallant style in its dance-like singability with focus on underscoring the meaning of the text above all musical tricks. Instead of ending with a chorale it ends with an “aria” which highlights this singability. Initially this aria always sounded very chorale-like to me because of the way each phrase ends with a fermata, but when you analyze it a little more it becomes apparent how different it is. Chorales usually only have one note per syllable moving mainly in a step wise fashion, while this aria has leaps and scales, several notes to a syllable in places. It’s slightly more florid than a chorale, more passionate. It is truly an aria for choir. Performing such a modern sounding motet at a German funeral was something of a rarity and leads musicologist Martin Geck to wonder if it was composed specifically for someone who was known to be a fan of more forward looking music. You can read an extended discussion of this motet here. Here is the text in German and translated into English as used by Bach:

This is one of several motets by Bach for double choir, but due to the back and forth nature of the choirs in the “du bist der rechte Weg” part I’ve decided to divide the puppet screen to show how the two choirs are separate but come together at the end.  One of the guru fish One of the guru fish We follow two goldfish as they flop around on the bathroom floor, fall into the drain, struggle through the house pipes, then the main water line, and through the sewers. The sewers follow “der saure Weg,” or “the bitter way,” and the fish meet several strange and creepy creatures there, including a cockamouse and the Loveland Frogman. The goldfish splash out of the sewer and end up in the river (the Elbe on one side and the Rhine on the other, two German rivers that lead to the sea) where they are met by two colorful koi who I call guru fish. The gurus set them off on the right path to follow the river and get out of the way of the bubbling sewage. As the choir trades off singing “du bist der rechte Weg,” or “you are the right way,” various river creatures make an appearance to accompany the goldfish on part of their journey. These creatures vary from mammals to birds, to other fish. In fact this motet contains more puppets than the other two due to the split screen aspect, but they mostly make brief appearances. This part of the motet is extremely lulling and meditative. In fact I found it kind of boring before, but after practicing the timing of the scroll over and over I discovered what this music really is. It’s a meditation, and what better way to enjoy a meditative trance than to follow the river? Eventually both the Elbe and the Rhine empty out into the same place: the North Sea. As the aria begins the split in the screen disappears. The choir comes together as one, and the rivers become one sea. The guru koi come back to lead the goldfish into the sunset. I love that Komm, Jesu, komm is the one motet that is so very much about pathways, making it fairly emblematic of the entire motet puppet project as a whole. I invite you to imagine these guru fish as any spiritual or philosophical leaders who appeal to you be they Jesus, Buddha, a wise teacher, a spirit guide, or even Karl Marx.

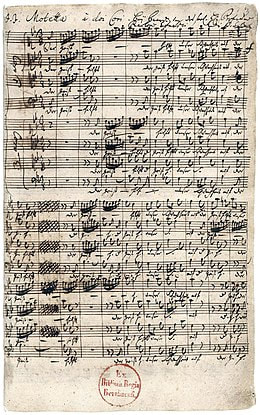

J.S. Bach's manuscript for Der Geist hilft J.S. Bach's manuscript for Der Geist hilft Der Geist hilft unser Schwachheit auf is the only motet for which we have not only the autograph but also almost all of the performance parts, and we know (almost) exactly when it was performed and why. Der Geist hilft was written for the funeral of Johann Heinrich Ernesti who was the rector (or headmaster) of the Thomasschule where Bach was the choirmaster. Ernesti was also the professor of poetry at Leipzig University, and in the early 18th century that primarily meant studying ancient Roman poets. He gained fame for his writings about Cicero (ironically not a poet.) Ernesti did write poetry himself, but primarily in the form of Curriculum Vitaes for his students, apparently a strange but common practice at the time. A couple years after his death CVs would be required to be written in prose form as Leipzig University had had enough of this overly witty poetic frippery. As rector of Thomasschule Ernesti was a bit negligent, which might be why Bach liked him. We know that Ernesti died on October 16, 1729, but there’s a little bit more confusion as to when his funeral was held. It was somewhere between October 20 and October 24, and while his death was by no means unexpected it did happen suddenly, leaving Bach between 4 and 8 days to compose Der Geist hilft. At least the text was already chosen for him as Ernesti had specified he wanted the text for his funeral service to come from Romans 8:26-27. Here’s the full text of the motet in German and English:

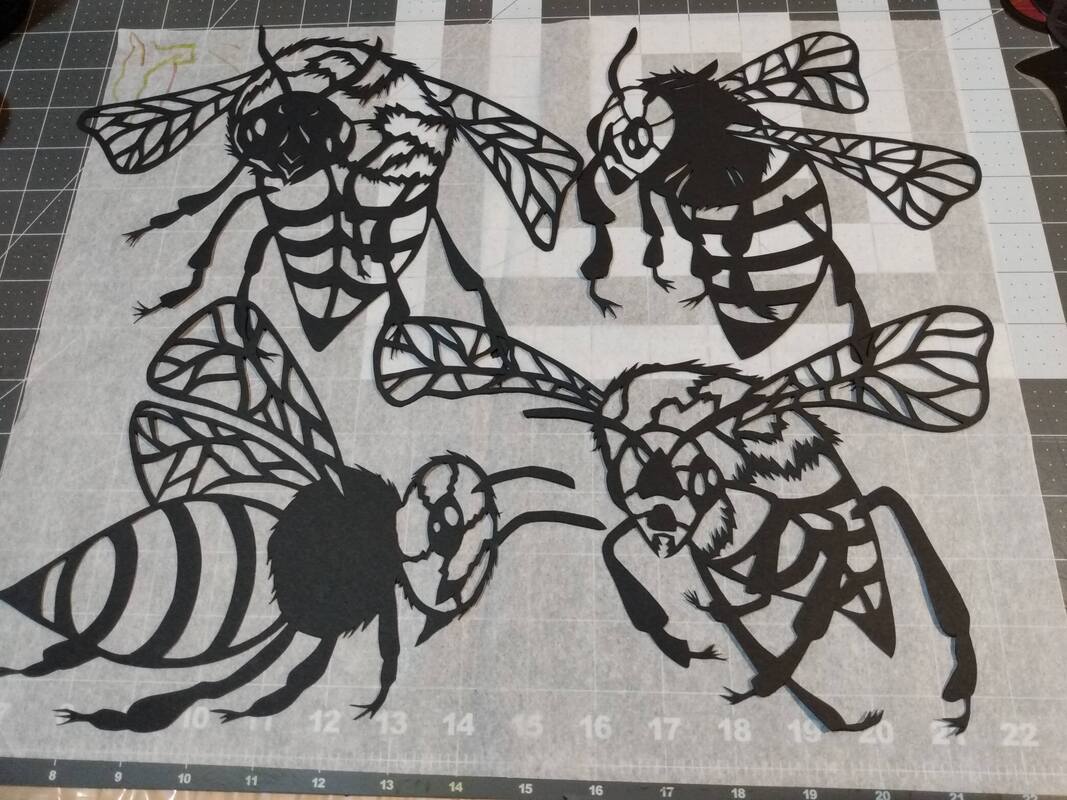

Komm, heiliger Geist Komm, heiliger Geist The words for the chorale come from the third verse of Martin Luther’s hymn, Komm, heiliger Geist, Herre Gott (the melody of this chorale is quite old, possibly related to a piece by Marchetto di Padua from the early 14th century.) The textual choice of this chorale was likely Bach's alone. He also used this chorale in his cantatas: Wer mich liebet, der wird mein Wort halten, BWV 59; and Er rufet seinen Schafen mit Namen, BWV 175. There is some speculation that while the chorale was definitely performed at the funeral, it may not have been intended as part of the motet since orchestral parts are not written for it, only choral parts. It’s possible that the chorale was sung a cappella at the graveside rather than at the end of the motet, but then again it’s also possible that the instrumental parts have been lost. Because Bach had such a short time to compose this motet it’s thought that he likely pilfered bits and pieces from pre-existing works. I mean, Bach was a genius who was also great at recycling his own work, so this isn’t wholly remarkable, but I can’t help but marvel as a singer how the chorus learned this piece that quickly! I think though that this partially explains why Bach used instrumentation in this motet, the only one for which instruments are explicitly called for (strings double choir one and reeds double choir two, and there is of course the requisite continuo part.) There are other reasons for using instruments too, mainly that this was a special solemn occasion that called for some extra musical oomph. It is also likely that Bach’s Thomasschule choir was joined by choral forces from Leipzig University since the funeral was held at the university church, the Paulinerkirche. The use of at least some instrumentation in motets may also have been German tradition, usually it was just organ or continuo, but since this is the only motet of Bach’s that has instrumental parts written out we don’t really know what kind of instrumentation, if any, was used for the others.  Johann Heinrich Ernesti March 12, 1652 - October 16, 1729 Johann Heinrich Ernesti March 12, 1652 - October 16, 1729 The conjecture around Bach’s reuse of pieces in the composition of Der Geist hilft is really interesting. There is a separate six bar composition on the back of the motet manuscript without words, which seems “cantata like” and has led musicologist Alfred Dürr to think it may have come from a lost cantata. It’s also possible that Der Geist hilft is a reworking of a cantata that Bach was already in the middle of composing (or even rehearsing), but when Ernesti died the focus switched. This would mean that the cantata used as a model for this motet never actually existed in a finished form. There’s also the thought that the opening section with the sopranos in each choir trading off motifs comes from a lost duet, but that is also pure conjecture. Bach was also clearly working with the text from memory because he forgot the word “selbst” and had to add it in later, which messed up his musical lines a little bit. You can read much more about all this here, but it’s really long, so search for “Dürr” to find the more salient bits. As I like to say, the first performance of a piece is usually not the best performance, so I imagine that this funeral performance was probably pretty rough. I’d also like to give a shout out to Anna Magdalena and Carl Philip Emmanuel Bach for all their hard work copying the parts, you guys rock! Personally, this is one of my favorite motets. It’s just so jazzy, syncopated, and fun to sing! I guess that’s another argument in favor of Bach parodying himself here because the music really does feel too joyful for a funeral motet. As far as the puppets are concerned Der Geist hilft represents the “path of wood.” You can read more about the overall concept behind the puppet show here. To recap briefly, I designed the puppet show so that each motet represents one path toward enlightenment (or unity with God, Source, All That Is, what have you.) Each path is based off an element, but I’m borrowing elements from various world traditions, so here we have wood as an element. The piece starts off with four squirrels playing in the grass at the base of a giant Douglas-fir tree. They begin climbing together, giving up and going back one by one until there is only one squirrel left. This lone squirrel braves all sorts of obstacles on his ascent including a raccoon, two crows, bugs, an owl, an eagle, and even a swarm of wasps. At one point he fights a couple of songbirds for a cage of suet that some crazy climber hung way up high in the tree. As the chorale begins the squirrel is up so high the clouds pass him, but he carries on, eventually reaching the top as it disappears into the light. I thought this a fitting metaphor for God helping our weakness. Squirrels aren’t the strongest beasts, but they do have their talents. As long as we are each aware of our own strengths, and believe in ourselves, maybe God will help us succeed on the path most suited to our abilities. The set for this motet, a moving scroll (or “crankie”) is definitely the star of the show at almost 25 feet long! That’s long, but shorter than the one I made for Komm, Jesu, komm. I made it to imitate climbing a tree, so I used math to figure out a very gradual forced perspective. The tree goes from filling the screen to collapsing into a single point over the course of 18 scenes, and I took great liberty with the colors and textures of the wood. My dad saw it and thought it gave off a lava lamp kind of effect. Some of the colors are most unwood-like, but it was definitely fun to paint! Why a Douglas-fir? I have a special relationship to these trees, and I visit them in parks whenever I can. I remember lying beneath one in Salmon Bay Park weeping and burning with fever after a breakup only to return to that tree years later to find it weeping too. I once wrote a poem that included a fir tree “clinging with sap and scent” only to find one the next day in Schmitz Preserve Park sparkling in the way I had envisioned. For me Douglas-firs are spiritual protectors and grief eaters. I'll leave you with the poem I’m referring to. It’s at least somewhat related to the concept of God, or spirit, helping our weakness.

You can catch the show, a collaboration between Paper Puppet Opera and Seattle Bach Choir, on Sunday, March 12, 2023 at 7:30 PM at Our Redeemer's Lutheran Church in the Ballard neighborhood of Seattle. Entrance is by donation only, so come early, and bring opera glasses. Oh, and March 12 also happens to be Johann Heinrich Ernesti's birthday!

The first puppet I made for this production: a carnation shown on a cat toy on the score of Lobet den Herrn The first puppet I made for this production: a carnation shown on a cat toy on the score of Lobet den Herrn Seems there isn’t much to say about Lobet den Herrn, alle Heiden, or BWV 230, historically. It is “Bach’s” only four part motet, and Bach is in quotes here because its authenticity is in question. Many scholars seem to think it is not by Bach, but perhaps by one of his sons or a student. According to Bach scholar Martin Geck in his book, Johann Sebastian Bach: Life and Work, it was likely written by Wilhelm Friedemann Bach or Johann Gottlieb Goldberg (as in "The Goldberg Variations"). Geck’s main argument is that the work sounds too modern, verging on the gallant style. Others claim it sounds too instrumental compared to the rest of Bach’s vocal works, and indeed it is one of the motets which explicitly calls for instruments that do more than just double the choir. Lobet den Herrn, alle Heiden was only first published in 1821 by Breitkopf und Härtel, and while the publishers claimed to have had access to the autograph score that autograph is long gone. Furthermore, just because it was in Bach’s hand doesn’t mean it was by Bach as he was known to make copies of works he particularly liked or needed to use. Nonetheless, it has been thought to be by Bach for long enough now that it has found its place among the other Bach motets and gets quite a lot of performances. For more historical information you can read this article from the Bach Choir of Bethlehem.  The text of this motet comes from Psalm 117, the only motet “by Bach” that uses only biblical texts, and is rather too celebratory to have been written for a funeral as most of Bach’s other motets were. We don’t actually know what occasion Lobet den Herrn was written for, but here’s the text in both German and English.

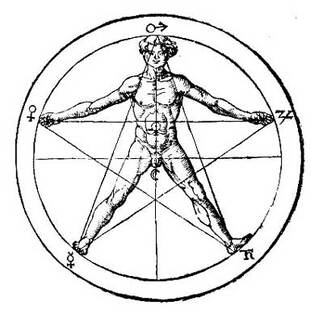

I have more to say on my shadow puppet concept for this motet. Lobet den Herrn, alle Heiden depicts “the pathway of light.” For more information on my concept for the puppet motets as a whole you can read my blog post here. The pathway of light does the most, I feel, to portray how united all of earth’s creatures are, and in my mind this is worthy of praise to our creator via the text of this motet.  The human body at the center of the pentagram by Agrippa The human body at the center of the pentagram by Agrippa The show starts with a single circle of light, then one by one rays of light are revealed around that circle. Stars with zodiac symbols in the center appear in those rays of light and remain rather static most of the time, as fixed stars. I used zodiac symbols as shorthand for the constellations they represent rather than to symbolize actual astrology. Personally, I am an astrological agnostic, but I wanted to show how we are all made from “star stuff,” and thus all connected to one another and to the rest of the universe. You will see a mixture that includes 8 six pointed stars and 4 eight pointed stars. Originally I made 12 pentagrams, but when we began rehearsing around Halloween it looked a little too satanic to perform in a church (one of my puppeteers remarked, "That was fun. We went to rehearsal and summoned demons!) However, there is a symbolism to the five pointed star that is relevant here. You can read more about it and its importance as a symbol to Pythagoreans here. The ancient Greeks, saw each point of the five pointed star as representing an element: air, water, fire, earth, and spirit (or some say aether or ideas). Together these elements create humans, so the center of the star, or pentagram, represents humanity. This is a perfect symbol for my motet project as a whole since humanity is placed in the center with Jesu meine Freude and the rest of the motets each represent an element. However, now that I want to do seven motets the symmetry changes and a six pointed star would be more appropriate. My arrangement of elements would be: light, water, wood, earth, stone, and air which together create humans. So in my symbolic world the hexagram at the center of a six pointed star would represent humanity. I'm also including 4 eight pointed stars that are meant to represent compasses since we are on a journey here and need something to keep us on the path. Once the stars move on, black and white flowers appear and dance about the rays of light rather chaotically, getting bigger and smaller. Flowers and plants are light eaters, and we eat plants, so in a way we are also vicarious light eaters. All of life is nourished by light in myriad ways. The dance of the flowers ends with the slow section where a single seedpod appears in the central circle, visited by a lone bee. Petals of red and orange appear around the seedpod as more bees come out. The seedpod gives way to a big purple iris. Leaves appear over the petals, the petals disappear, and colorful butterflies come out. When the Alleluia starts the rays of light disappear and we see a labyrinth of intertwining vines and leaves. The same black and white flowers we saw earlier come back bigger and in color, dancing about for a second before all becoming one big bouquet with the iris at the center. You can catch the show, a collaboration between Paper Puppet Opera and Seattle Bach Choir, on Sunday, March 12, 2023 at 7:30 PM at Our Redeemer's Lutheran Church in the Ballard neighborhood of Seattle. Entrance is by donation only, so come early, and bring opera glasses.

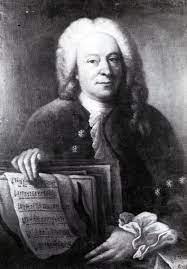

People often ask me when I talk about this project: what the heck is a motet anyway? Well, the definition of a motet has changed over the centuries, so this is not an easy answer. Because of this the renowned Bach scholar Philipp Spitta openly scorns the motet in his three volume biography of the composer saying that it never really refined and defined itself the way other old musical art forms have. Depending on who you ask even the origins of the term “motet” are in dispute. Most scholars today think “motet” comes from the French word for “word” itself, “mot.” In the age of the Notre Dame School, when polyphony was getting carried away in the 13th century, there was a lot of criticism from the church that the words of these crazy new choral settings could no longer be understood because of all these competing musical lines. Some of the clearer lines to the ear were the descant or plainchant parts, the higher harmonies and chants floating over what was often heard as cacophony below. There came a point when French poets put new words to these parts, and originally these were often secular texts. It wasn’t uncommon to even have competing texts written for these parts in several languages at once! The polyphonic parts below were preserved as instrumental parts, so the original motets have more in common with solo songs or madrigals. Here’s a more concise article on the evolution of the motet.  Manuscript from a rarely performed motet by Thomas Tallis Manuscript from a rarely performed motet by Thomas Tallis From here motets began to evolve into very different animals. During the Renaissance they became sacred again, and choral, with or without instrumental accompaniment. They also became grand showpieces that took that Notre Dame School polyphony to the next level. Motets became central sections to masses, so much so that masses were often named after the motet incorporated into them. In German speaking areas the motet texts could be sacred but non-biblical texts, and usually fell into one of two categories: a chorale motet or an aria motet. The chorale motet uses chorale texts and the structure of the motet is often dictated by the chorale in some way. An aria motet is a string of strophic arias sung by one or more soloists. Johann Sebastian Bach’s cousins, Johann Michael (also Sebastian’s father in law) and Johann Christoph Bach, wrote a great many motets which Sebastian studied and frequently performed himself in the course of his church duties. Give some of those a listen, the best of them are incredibly moving and awe inspiring.  Johann Christoph Bach, see any resemblance? Johann Christoph Bach, see any resemblance? By the time J.S. Bach began writing motets of his own the art form was already considered old fashioned, or at least very traditional and rather conservative, which is why motets were a good choice for funerals and teaching examples. Bach composed motets for both of these purposes, primarily the former, however Singet dem Herrn and Lobet den Herrn were definitely not for funerals as their texts are too celebratory. Singet was likely a teaching motet and there are still a lot of questions around Lobet, more on that later. There are six motets in the current canon of J.S. Bach’s works that are often presented and recorded together:

It’s extremely uncommon for all of these motets to be sung together on one live program, however, Seattle’s Emerald Ensemble did do this for their inaugural concert in 2016, which I had the good fortune to attend, and it is still talked about today for the remarkable feat it was! That being said, Bach never intended for these pieces to go together in this way, and the catalog numbering system only indicates their musical genre in a weird haphazard order unrelated to their dates of composition. There are also additional motets that are either: actually written by Bach, once considered to be written by Bach but actually composed by someone else, or parodies of other Bach pieces put into motet form. These are as follows:

You can read more about all of these here. From this list of extra-canonical motets only Ich lasse dich nicht; O Jesu Christ, mein Lebens Licht; and possibly Sei Lob und Pris mit Ehren are actually by Bach. Now that all that historical background is out of the way I want to talk about my concept for a puppet show around the motets. It’s an idea I’ve been kicking around for a few years now, but without any real solid concept. One day at a Seattle Bach Choir board meeting I mentioned this idea and how I’d love to create a puppet show for them not really thinking they would take me seriously. Seattle Bach Choir had a new director who had just finished his first concert with us at that point, Dr. Daniel Mahraun, and he was actually very interested in this idea! Now I had to flesh out a real concept for this puppet show. We sat down to discuss the idea in February of 2020 with a plan to put it on in 2021, but then the pandemic hit and everything was delayed. The show is finally happening three years later! I hadn’t yet created a puppet show around Christian texts, and this posed an interesting issue because I am not Christian myself. My concept for the motets became a sort of personal spiritual manifesto in shadow puppet form, and I say “sort of” because my focus is on the more universal aspects of my spiritual system. For years I created translations (or more often simply rearranged existing translations) for Seattle Bach Choir’s concert programs, and these motets were frequently in the repertoire. I joked that there are only two themes present in them: praise God, or my life is awful and I can’t wait to die. However, my weird esoteric spiritual background colored my translations. We frequently performed works with Christian texts that had standard English translations, but I would look at them with a different eye and bend them a bit toward the esoteric whenever I could. I’ve never admitted it until now, but there ya go!  Imagine this guy but with a really long beard Imagine this guy but with a really long beard The overarching concept I came up with for a motet puppet show is about pathways to enlightenment and the spiritual unity of all life. This all goes back to a dream I had when I was between 11 and 13 years old. I dreamed that I was in a prison cell with my brother and we were visited by an ancient medieval knight dressed in white armor with a red cross on his breastplate, long flowing white hair and beard touching the floor. He said only, “there are as many paths to enlightenment as there are rays of light to the sun.” In retrospect this must have been a spirit guide visitation, and apparently a member of the Knights Templar flouting the importance of his beard. It left a lasting mark upon me and I still say his phrase all the time. I think it’s important to recognize everyone’s personal truth. In my own spiritual system reincarnation plays a big role, which means (as I see it) from life to life we have experienced and believed in many different faiths and followed many different religions. Does that mean they’re all false? I would say completely the opposite, what if they’re all true? Could there really be that many different truths, and doesn’t that negate the very concept of truth? Maybe, but what if all these truths lead to the same place? In my system the truth we hold dear right now is exactly the truth we are meant to have at the moment. As long as we are harming none then our belief filters are doing an important job. I don’t think we can control our beliefs very well as humans, not to say that they don’t change sometimes, but they do provide our consciousness with a user interface, and we can’t operate on earth without one. For the puppet show I thought about all the forms in nature that create pathways: rivers, roots, branches, rays of light, gusts of wind, and even the veins of the human body. Because Jesu meine Freude is composed as a musical palindrome I wanted to put it at the center of the motet puppet show. This would make the central fugue, ihr aber seid nicht fleischlich, sondern geistlich (we are not of flesh, but rather of spirit), the central point of the puppet show. In my mind Jesu meine Freude follows the pathways of veins, nerves, and bones in the human body, and this fugue would be a battle within the heart itself. A woodpecker and a beaver from Komm, Jesu, komm The only other rules I had were that Lobet den Herrn should start the show and Singet dem Herrn should end it because both of these motets are songs of praise. Lobet would involve the path of light with stars and flowers, and Singet the path of air filled with breezes and birds. Der Geist hilft represents the path of wood (as seen by a squirrel climbing a tree) while Fürchte dich nicht represents the path of roots with a worm digging through the dirt. Komm, Jesu, komm shows the path of water represented in the journey of goldfish from sewer to ocean. The order I have in mind is: 1. Lobet den Herrn 2. Komm, Jesu, komm 3. Der Geist hilft 4. Jesu meine Freude 5. Fürchte dich nicht 6. Singet dem Herrn For me there’s a thematic echo between Der Geist and Fürchte because of how trees and roots are related, so they’re reflected on either side of the center making a thematic palindrome around a musical palindrome. But in order for this to be a real palindrome with a center I would need an odd number of motets. A few months ago I discovered Ich lasse dich nicht and got very excited! Here is a seventh motet to complete my palindromic idea! It would go just after Jesu meine Freude, but I’m not yet sure what the theme would be, a system of pathways related to water in some way. Lava maybe? Liquid stone? Caves created from water erosion? Glaciers? All of the above?  A douglas fir cone from Der Geist hilft unsrer Schwachheit auf A douglas fir cone from Der Geist hilft unsrer Schwachheit auf It’s a big idea, but like I said before it’s very rare that all six motets are performed by one choir in one concert, let alone seven! However, I am hoping to one day gather together two or three chamber choirs to share the load and perform all the motets in order that way. In the meantime you can catch the first three with shadow puppets and live singing by Seattle Bach Choir at Our Redeemer’s Lutheran Church in the Ballard neighborhood of Seattle on March 12, 2023 at 7:30 PM. That Sunday is also the start of daylight saving’s time, so remember to spring ahead. Entrance is by donation only, so get there early to claim a seat, and bring opera glasses if you have some as the puppets are somewhat dainty. Watch this blog for more about these three motets. I’ll be discussing each one individually over the next few weeks. In case you’re interested, here’s a partial discography of Bach motet recordings we puppeteers have been practicing with. We like to stay on our toes, so we’ve been alternating between several recordings.

Guess I should keep up on this blog a bit more. Well, keeping in the same vein as the last post, here is another "meditation with Franz," this time about his song Du bist die Ruh. I turned this song into a puppet show last spring and combined it with nine other songs I fell in love with while working on Winterreise into a show I call "Schubert Scraps." I took this show to Europe with me and performed at a house party in Bonn to rave reviews. Huzzah! I hope someday we can all travel again. I want to perform at your house! Here's what I experienced in this meditation: I saw a long hallway leading to a window at the end. Franz appeared beside me and took my hand. As we walked down the hallway I could see the walls were decorated with intricately carved dark wood. At the window we stopped and glanced at the view. We were high up looking over rivers and hills, but quickly Franz led me to the right where there was a bookcase. The bookcase was a door, which he opened and there was a fireman’s pole behind it. We slid down the pole and were in a rocky cellar. It was very dark, so he took up a torch. We continued down the close rocky path and turned again, now the walls were even closer and we had to crouch to keep from bumping our heads against the ceiling. It felt hella haunted down there, even though I was technically standing beside a ghost. At the end of this very tight rocky hallway there was another door with a frosted glass window. Franz took out a key and opened it. Behind the door was a very small room with vaulted ceilings like a tiny church. Before me was a small book shelf sitting on top of a cabinet built into the wall. Above me was a crystal star in the center of the vaulted ceiling with crystal pendants hanging down. I looked to my left and gave a start. A bejeweled skeleton sat there dressed to resemble a bride. I looked at her more closely. Sapphires were her eyes and she had a daisy crown made of pearls, diamonds and gold with a veil flowing down from it. Gold wire curled over her cheeks and her fingers were covered in rings. She wasn’t quite wearing a full wedding gown, but more of a white lace negligee. A bouquet of dried white roses hung above her. “What is this?” I asked. “I wrote Du bist die Ruh to the love I wished I had. This is her, but of course nothing remains of her but the decoration of the song she inspired,” Franz said. I knew he wasn’t talking about a real specific person per se, but of a template, the internal collage of love that inspired all his songs. “Let me show you something.” Franz touched the bookshelf in front of us and it opened up like a door too. Behind it was a vast collection of cups on a tray that could be pulled out, but it went far deeper into the wall than the room was wide. He took out a cup and handed it to me. It was gold with large jewels around the rim, goblet like. “This is Du bist die Ruh,” he said and told me to drink from it. I tipped the cup to my lips and looked into the bottom as I drank what seemed to just be water, but the water wasn’t the point. That water appeared to me as the sea with mountains on either side. The full moon rose in the center and a lotus hovered before it just above the sea. “Wow!” I exclaimed as I put the cup down. Franz then placed a ring on my finger. It was a pink glass lotus with gold tips on the petals. One small diamond glittered upon it like a dewdrop. Then he took out another cup to hand me. “These cups are all of my songs,” he said. “Deep feeling fashioned them all, but the feelings no longer remain, only the art. This is how all of creation came to be. Now you are welcome to fill them with your own feelings.” This cup was another goblet with a stem that appeared to be two golden hands whose fingertips became tree branches clutching a frosted glass cup with a wide lip. I lifted the cup to drink from it and was struck by the image of the brightest whitest sun I had ever seen inside. The beams burst forth like crystal with rainbow edged beads of light. I don’t know what I drank from it, it didn’t matter. “What song is this?” I asked, but Franz didn’t seem to want to tell me. I guess it wasn’t important, or maybe I’ll find it later. I handed the cup back to him and he put it away. He closed the bookshelf cabinet. It appeared as if cobwebs floated all around us, but even these were merely the ghosts of cobwebs. Franz pulled out a book which was very old and much loved. It was a book of Schiller poems. “These books are all the poems that shaped me, and my journals and diaries too.” He opened the book and it was covered in footnotes written in pencil. He put it back and we turned to the right where there was another similar bookshelf. "What is this special place?" I asked. "This is the shrine to my dead feelings," Franz said matter-of-factly. He then opened this shelf in the same odd manner as the former, and inside was the same long tray but full of flowers of every color and variety. Butterflies fluttered just above them, but the flowers were all dried and the butterflies were made of paper. “The ring I gave you is an analogy for this,” he continued. “The lotus rises above the muck of emotion, but we mustn’t forget the feelings that forged us. The diamond dewdrop on that lotus can be seen as a single tear. These painful feelings are capable of creating the deepest beauty, and in so doing they themselves become beautiful.” I looked at the skeleton again and noticed that now behind her was a stained glass window where there had been the bouquet of dried flowers. I realized that while this room was a shrine to dead feelings it was still very much alive and changing all the time. I suppose that makes sense. The way we see how we felt once upon a time is always changing. Our personal histories are constantly being rewritten within our own subconscious. I was beyond words. But still I realized I hadn’t gotten all the information I wanted on Du bist die Ruh. “But, I wanted to know more about your artistic choices for that song,” I said. “Why did you choose the modulations and motifs you did, especially in that piano intro.” As the ever flattening and descending piano line played in my head I got an image of uneven stone steps leading down deep into a human heart where I opened a wrought iron gate and closed it behind me. As the piano line jumped up and fluttered I lit a candle and filled the heart with my light. Aha!  Feelings are fleeting but art is eternal. Our emotions are but wax molds that melt when shaping copper. The copper holds their shape, even when the feelings themselves are lost. I got up and put on a CD of Elizabeth Schwarzkopf singing Schubert lieder. One of the songs was Ganymede. Now things make some interesting sense. It would appear Franz saw himself as Ganymede, not just in the homoerotic sense (look it up), but as literal cup bearer to the gods - most beautiful among mortals for his mind and therefore abducted, inspiration forced upon him as a form of seduction so he could always be giving his art to the immortals. No wonder Franz has this collection of beautiful cups. Our production of Winterreise opens tomorrow, so as you may well guess I'm a bit busy, but I wanted to tell you about this in the half hour before I have to leave for our dress rehearsal.

I took all 24 meditations I had on this great work and compiled them into a book, which I will be selling at the show. It's called "Winter From Above: Meditations on Winterreise with Franz Schubert." You can also get it here if you can't be at the show. I won't lie, this book is really weird and makes me sound like a loon, but I thought there was some information in these meditations worth passing on, regardless of what you may think about me and whatever neurosis you may perceive me to have. It's unlike any book on Winterreise out there. Think of it as kind of an adult version of The Little Prince which takes you on a surrealistic journey through the spirit world with all its beauty and contradictions. Many of the puppet scenes you will see this weekend come directly from these meditations, and some were not visually translatable, but still worth writing down in my opinion.  This is gonna sound weird, but when I have trouble figuring out what to do with some of the Winterreise songs I meditate and just "ask Schubert" directly. What can it hurt? I just breathe deeply three times, picture a circle of white light open up, and BAM, I'm in heaven chatting up a genius. I'm just goofing off after all, right? Well, it turns out to be extremely helpful. The meditations are supremely vivid, poetic, and it turns out Franz is incredibly wise and full of love and passion. He will usually turn these horrifying songs into a teaching moment to help me with whatever troubles I'm dealing with or have dealt with that are relevant. I want to write a book that includes all of them, but for now I have a puppet show to create. It's amazing what happens when we give ourselves the freedom to be strange, and I'm finding my subconscious to be a far more stunning place than I had ever imagined. Next time you wonder what was going through a great dead artist's head maybe you should just "ask them." Unfortunately I only started trying this technique when I got to song 7, but I may go back and meditate on the first few later...at least for the book.  I had some questions about Auf dem Flusse and Rückblick. Franz took me to a wintery landscape and we stood under a linden tree in full bloom, but in the snow. We were surrounded by snowy mountains and wearing heavy fur lined clothes. There was a frozen river winding through the valley as far as the eye could see and we walked up to it. I had given some thought earlier to the image of the broken ring in Auf dem Flusse as being a broken path that also provides the opportunity to forge a new path. “I like your idea of what the ring represents,” Franz said. “The wanderer in Winterreise has his path proscribed for him in his expectations of marriage, and when that path is broken he doesn’t know what his path looks like anymore. He’s afraid, confused, and maybe a little excited, but he wouldn’t admit that to himself yet. Most people see the path of the ring as safety. They know they will be taken care of and they don’t have to think too hard about their life path anymore. They don’t have to forge it as actively. They know what to expect today, tomorrow, ten years from now. There’s nothing wrong with that, and it is appealing, but you and I are a bit different. We need to forge our own path and have the liberty to change it as we feel fit. What path diverges from that broken ring?” I had an image come into my head of winding paths growing like antlers out of the cracked ends and sighed, “Oooooh!”  “How do you see Rückblick, Franz?” “That song is all about hyperbole. He remembers his leaving the town as being much worse than it was and he remembers arriving there as being much better than it was. If you remember the first song when he does actually leave it’s very calm. Sad, but calm. There are no crows throwing snowballs at him. There’s wind and some snow falls on him, sure, but it’s nowhere near as bad as he is remembering in Rückblick. This song is about extreme contrasts and about how our memories are easily distorted.” “Can you give me some ideas for the puppets with that?” “Ha! That’s your job. I’m not getting in the way of your creativity, just guiding your inspiration. You’ll come up with something great.”

I thought it was odd that there would be a graveyard in heaven, but Franz said they have all things there, this was for inspiration because I have had many a worry about what the heck I’m going to do with the song Das Wirtshaus. He simply reminded me of all the time I’ve spent in Austrian graveyards. Truly, I’m a genuine connoisseur of them. He showed me the contrasts between the simple graves and the large gothic noble graves, the grotesque and the touching. They were practically parading before me. I was thinking how I need to find a way to have things pass before the screen like a crankie but without having to put in the crazy amount of time that crankies require, that and they can be blurry when they’re behind a screen. A parade of graves seems like a good idea. This may be the only time you ever hear me say that.

Gute Nacht, opening scene Gute Nacht, opening scene This is really what Winterreise is about. You can say it is about a search for meaning, or an attempt at transmutation (for better or worse), and it is about all these things, but beyond all that it is about living through your pain and experiencing every flavor of it because not to do so would be worse. Sure, our wanderer could have left that house and gone on to another one, found love there; or maybe buried himself in his work, whatever that might be; or even have become an alcoholic or opium addict…but he doesn’t. Many of us have done these kinds of things in times of grief, but the grief always resurfaces, often in awkward ways. Men especially are taught to be stronger than their emotions, that giving into them is weak and to be avoided at all costs.  Deer Taking Shelter in Winter - Gustave Courbet Deer Taking Shelter in Winter - Gustave Courbet There is a temptation to view the wanderer in Winterreise as weak because he is always talking about his feelings and his longing for death. It’s easy to see this as wallowing. Honestly, we don’t know how much time has elapsed on his journey between the first song and the last. It’s probably longer than a day, but beyond that is it a week, a month, two months? How long must someone wander through such pain before we call it wallowing? Now that the science of psychology is better understood there is a push for greater acceptance of mental illness and trauma, less judgment on those who won’t just “get over it” whether their trauma be great or light in society’s eyes. We still have a long way to go toward completely rejecting the stigma of “excessive feeling” but we’re on the path, and at least we’ve expanded our understanding of PTSD so it’s not a disorder tied to a specific type of objectively severe trauma but is linked to the way an individual reacts to their own experiences. Most telling is that the wanderer in Winterreise doesn’t even attempt suicide. He is tempted many times, and often disappointed that he won’t just die of natural causes. It is especially interesting that he doesn’t commit suicide when it was such a common Romantic era trope to kill oneself over unrequited love. What does this tell us? For one thing, this wanderer is anything but weak (the concept of death vs gender and what this says about strength vs weakness is explored by Schubert and his friend, Josef Spaun, in two other songs which are clearly related to one another, but I'll save that for another post). Winterreise's wanderer wants to experience the bitterness of his situation to the last drop, and he is not staying alive for hope that his lot will improve. He doesn’t seem to have such hope, but he does seem to have an almost scientific curiosity about what might come next. It would appear that a part of him is an objective observer to his own pain, like when his tears turn to ice in Gefror’ne Tränen and he realizes he didn’t even know he was weeping. In this song and the next one, Erstarrung, he is terrified about what a lack of pain or what getting over his sweetheart would mean: would it mean he never really loved her and he is therefore incapable of feeling true love? Would it mean that without the pain of rejection there would be no other feelings beneath that? These issues come up in many of the Winterreise songs.  Illustration from The Snow Queen - Arthur Rackham Illustration from The Snow Queen - Arthur Rackham I understand what this is like. There have been very few times in my life when I didn’t have a crush on someone. For those couple of months when I didn’t I felt very strange, almost like a robot (hence the wheels and gears you may see in my interpretation of some of these songs). It was nice in its way, life felt stable, but also passionless. There have also been many times when I’ve been extremely reluctant to even try to get over someone because I was afraid of what that would say about my feelings for them. Once I fall out of love with someone that love never comes back, and the finality of that is scary. I always wonder at all those other people who can meet a former lover or crush later in life and fall in love with them again, it just seems so unreal to me. The fear that falling out of love with someone might mean I never truly loved them to begin with is also worrisome, and of course that also forces me to ask if I’ve ever really been in love or if I am in fact incapable of experiencing love at all.  Snow Near Honfleur - Claude Monet Snow Near Honfleur - Claude Monet Last month I sat at the bar where I and my former fiancé would often hang out and realized that I thought I had finished my personal winter’s journey, but I still have so terribly far to go. It’s no longer about trying to get over him, and hasn’t been for a long time, but it’s about finding my path. Where is my path if romantic love is not going to be a part of it? What does that mean for me? I hope you don’t pity me for saying such a thing. It’s just an objective observation. Romantic love is fun, but it doesn’t work for me. In Winterreise we see something similar in the difference between Part One and Part Two. Part One is mostly about processing the pain of the break up. Part Two is mostly about finding a path outside of romance, human companionship even, and wondering what such a life would be like and what it would mean. The wanderer laments much about how he is not like other people, how he can’t share the same dreams, the same paths, and this contributes to his loneliness in the second half. This sheds an interesting light on what his break up actually meant for him. Many of us think of ourselves as “weirdos,” too weird for anyone to possibly love us. For these weirdos break ups are especially painful because we never understand how anyone could have fallen in love with us to begin with. These weirdos come in many forms. Maybe you are an artist, or have a mental illness, or strange habits, or perhaps you are a nerd, or are obsessed with some niche subject that no one ever wants to talk with you about. Honestly, this is most people! This is why you may see this winter’s journey as your own. Weirdos are constantly striving to understand themselves and why they can’t connect with others the way they wish they could. While love is always a miracle, it is a much bigger miracle for a weirdo who has convinced themselves they are unlovable the way they are, and it is a much bigger loss when that love is taken away. Clearly, for some reason the Winterreise wanderer considers himself to be a weirdo.  Gute Nacht last verse Gute Nacht last verse I definitely feel like one of these people who is too weird to be loved. I also recognize that much of this weirdness is my own choice. You see, we weirdos are actually extremely romantic people. We may seem cold and aloof regarding potential romantic prospects, but we love very deeply. We just feel like we’re constantly faced with the horrifying reality that in order to make such love work we will have to give up an essential part of ourselves. While the thought of living a life without love is painful, the thought of giving up that part of ourselves for love is even more painful. Ian Bostridge in his book, Schubert’s Winter Journey: Anatomy of an Obsession, makes an interesting assumption about Schubert’s supposed love for the soprano Therese Grob. I agree with his assessment that Schubert definitely wanted to marry her but couldn’t because the marriage law at the time required the man to make a certain amount of money before a marriage license would be granted. Schubert clearly lamented his inability to make enough money to marry her, but what Bostridge questions is how deep was Schubert’s love then to begin with? If he loved Therese truly wouldn’t it have been worth it to him to find a job (any job) that would have paid him enough to marry her? This is a choice I myself have faced, not because of any laws, thankfully, but because my fiancé was concerned that I didn’t make enough money as an artist for us to get married after all, and this is part of the reason we broke up. I could have genuinely tried to find a job that would have made more money, but I chose to focus on my art. That doesn’t mean the break up wasn’t painful, or that I never really loved my fiancé, it just means that I needed my art in my life more. I see that this was the kind of horrible choice Schubert faced in his youth How much did this incident inspire his setting of Winterreise? How much will my similar experience inspire my own interpretation of the piece with shadow puppets (the creation of shadow puppet operas was also, incidentally, my way through the pain of that break up)? Did Schubert experience the same wondering, questioning of priorities in life and love? Personally, I don’t think either Schubert or I regretted the decision to make art the priority over romantic love (Schubert even once referred to music as “the beloved,” which makes me smile), but it does make us “weirdos” in the sense that our priorities are/were just different from what it is we’re “supposed to” want out of life. This could also be what makes the wanderer’s journey through endless winter so complex. Sometimes life is not about choosing what will make us happiest, but about choosing what will hurt the least and give our lives the most meaning. Art is so often about creating meaning, and art is a great substitute for happiness. Art is always a way through the pain, even if we never make it all the way through to springtime.

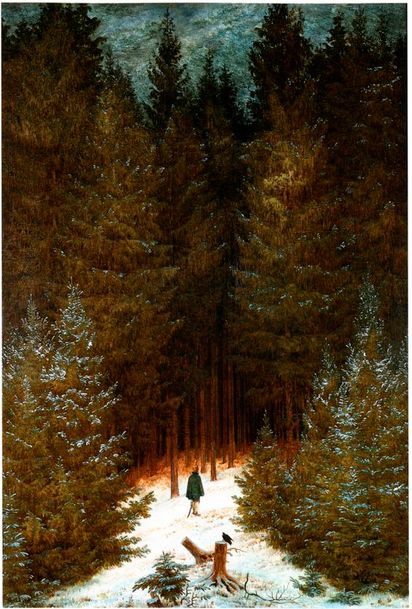

Well, I completely forgot that I started this blog a year and a half ago! I regret that I never posted anything regarding the creation of The Isle of Merlin last year, but I am excited to announce that I will be mounting a shadow puppet production of Schubert's Die Winterreise! That may sound odd, but when you think about it, it makes perfect sense. I feel that shadow puppets lend themselves beautifully to bleakness, and I've been dying to depict a gloomier work through this medium. I have been considering Mozart's Requiem or Pergolesi's Stabat Mater toward this end, and these pieces may well materialize at some point, but I've been twizzed out over Schubert over the past couple months, and have been having a strangely wonderful time delving into this work. Plus it has the advantage of requiring minimal forces, which would make it financially feasible to produce, and I can puppeteer since I don't actually have to sing it!  Caspar David Friedrich is my favorite German romantic painter ever! You will see a lot of him in this series of blog posts. Caspar David Friedrich is my favorite German romantic painter ever! You will see a lot of him in this series of blog posts. What exactly appeals to me about this work? I just recently got all my CDs, all five shelves of them, into my small bedroom, when they had been languishing in storage for the better part of three years. I discovered that I have a whopping five recordings of Die Winterreise, and I had never given a serious listen to any of them! Us youngsters, which I define as under the age of 50, have a hard time listening to music and doing nothing else. This is a skill that is really an art. I had to date a man twenty years my senior to realize how important it is to spend time genuinely listening to music while doing absolutely nothing else. These songs are not immediately catchy or even necessarily melodic at all times, generally through-composed, and they often require attention to the poetry behind them to be fully appreciated. I've taken to a habit now in listening to Schubert's songs where I will listen to each one at least three times: once for the vocal melody, once for the poem, and once for the accompaniment. The accompaniment is often the best part, and it's not uncommon for me now to listen just for the accompaniment most of the time. I find this to be especially true in Die Winterreise. For me the piano says so much more than the vocal line, it's what really brings the poems to life. What secretly appeals to me about Die Winterreise is very personal, and kind of funny in a tragic kind of way. Back when I was in college trying to be a painting major, one of my assignments was to create a white painting. Our teacher would take us to the slide library at the University of Washington once a week to show us slides of masterful paintings on a certain technique she was showing us. I would always get so inspired by these slide shows that apparently I would express myself too much. One week she was showing us how many colors could be depicted in "white" and then we went back to the studio to paint an all white still life. I abandoned myself to highlighting all the colors I could see in "white," so many blues, greens, and especially pinks! Practically neon in their shimmering dance, it was an exuberant delight for me to see this vivid panoply of color in what was supposed to be the absence of color. The teacher passed by and gazed at my work while I was inspired by this dizzying array of chromatic joy and said, "that is...simply...awful!" I was forced to tone it down into the most mediocre piece of crap I had ever seen. As soon as this class was over I decided to become an art history major instead of a painting major because at least then I would know what had already been done so I wouldn't repeat it. This production of Die Winterreise is my attempt to reclaim the color white for myself! There really is so much color in white! I want to show you all the whole rainbow, plus some. Furthermore, while white light contains all colors, the same can be said for love. The truest, most spiritual form of love is just love, all white, containing all colors. It is a human need to classify and label love into its individual colors: friend, lover, brother, teacher, mother. Spiritual love doesn't delineate, it just is. I feel like this is the ostinato behind Die Winterreise (one of several: the motif of wandering, and that of staccato, frozen dripping being others) that true love is really all there is, a blank canvas for us to paint our expectations upon, whether they be for good or ill. Admittedly, on the surface, Die Winterreise can seem a little bit too thematic. There is a lot of repeating imagery, or at least it is a variation on a rather limited theme, and the color white can be seen as either very limited, or very freeing, depending on your perspective. It is a trip deep into the core of heartbreak, and I know we've all experienced it...don't pretend you haven't! I know I have, and I emerged alive, if only barely. Transmutation is key. Sometimes I like to wander through the park and have pretend conversations with Schubert, who I sometimes affectionately call "Franzie Pie" about random things. I asked him once about Die Winterreise...is it really just a 24 poem pity party? He said, "Oh no, it's so much more than that! It is all about transmutation. Grief can only be transcended through art. Art should ultimately transform into other beauties. Notice how the wanderer is constantly making his grief beautiful. Sometimes he remakes his sorrow anew into drawing, poetry, even unto other gods themselves! The cycle ends with Der Leiermann because the wanderer realizes that his sorrow can be turned into song. This is the ultimate goal." I literally stopped in my tracks upon the trail at Carkeek Park and said aloud, "Yes! Wow! That's it!" Die Winterreise is truly alchemical. Every artist turns their grief into true art. I even once lamented as a teenager that I had had a "happy" childhood, which would make the creation of true art much more difficult. Luckily, I wasn't as happy as I thought I was, and life only went downhill from there, so plenty of art in varying degrees of quality have since sprung forth from my fingers.  Snow in Mountains by Hans Gude Snow in Mountains by Hans Gude This all comes back to how the heck I'm going to approach this work as a shadow puppet opera. I want to see the profound truths, the deep wisdom behind the pain in this work, the unfolding into greater beauties. I like the idea of responding to poetry with more poetry, so to bring that element of hope, and maybe even a greater, more esoteric representation into Die Winterreise, I've decided to respond to each poem with one of my own, an answer in the guise of a spirit guide. So I will present these responses in order. If I was watching over a poor soul like Wilhem Müller or Franz Schubert as a spirit guide, and they were speaking to me in these poetic tropes, what would I say to them? Gute Nacht (for a translation of the original see here)

To me you have never been a stranger, nor shall you ever be. January is as beautiful as May, though its pearls are invisible upon the snow. Your lot has always been to seek, but what will become of you when you find? Behind every shadow is a light. Beyond hoof prints trots the deer. You are feral but unforgotten, a master unto himself. Love flies from candle to candle and alights even upon the darkest wick. Your heart is a true compass, wiser yet than my words. Though you close this gate behind you in the dead of whitest night, one day you’ll say good morning to your fairest hidden light. Check back for more poetic responses. |

AuthorHi, Juliana Brandon here. This is where I let you peek behind the scenes here at Paper Puppet Opera. See works in progress, rehearsal snippets, and learn more about the history behind each production. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed